Recording calving glaciers in Greenland

Sound recordist Thomas Rex Beverly uses Sennheiser gear to capture spectacular audio

Thomas Rex Beverly’s 90 plus nature sound libraries have been used extensively in the world of television, games, apps, museum exhibits and on high-profile film productions such as CODA, The Last of Us, Jack Ryan, Star Trek: Picard, Yellowstone, and Frozen II. As a nature sound recordist and composer, Beverly inspires listeners and hopes to help preserve precious natural landscapes and their breath-taking soundscapes for future generations. His latest expedition took him to Greenland in 2022, with Sennheiser MKH 8020, MKH 8040 and MKH 30 mics as well as HD 280 PRO headphones being his loyal audio companions.

Beverly’s love for the Arctic was ignited when he went to Alaska in 2019, where he had seen his first glaciers, but had not explored them up close – that was to change with his Greenland expedition.

“There has been a lot of emphasis put on documenting receding glaciers, but every time I’ve seen videos of these huge calving events, the audio was just below average. Often it would be just off-the-camera sound, or even no audio at all. I wanted to capture those sounds and share them with others. Greenland is a magical place to record those sounds,” Beverly shares.

With him in his nature adventures is a pair of closed Sennheiser HD 280 PRO headphones. “I've been using them for a long time, as they offer a flat frequency response across the spectrum and great isolation. HD 280s also hold up well outside, and I’m usually in extreme temperatures with a lot of humidity. I love the isolation as it allows me to monitor while being in the field.”

Beverly’s main recording rig comprises a double mid-side set-up with a Sennheiser MKH 30 figure-of-eight and two Sennheiser MKH 8040 cardioid condenser microphones. “You have a front and a rear mic, which in my case is a pair of 8040s, and the side mic is an MKH 30. This has been my ‘go-to’ rig, as you can do everything from a close-up animal recording to recording surround sound, all in one blimp. Plus, it’s a compact rig, which is important for me as I always have to think about how much gear I can actually fit in my backpack. Another benefit is that Sennheiser mics do really well in extreme temperatures and humidity. After having them for over six years, recording in the wild at least eight weeks of the year, they are still going strong!”

Beverly also used four additional MKH 8020 mics in spaced omni set-ups in various configurations to record the calving of glaciers, icebergs breaking up and general ambiance. As well as his Sennheiser set-up, Beverly also used multiple recorders, hydrophones for underwater recording, and Geofones, “which are basically contact microphones that I can stick into the glacier to record some of the sub-bass sounds.”

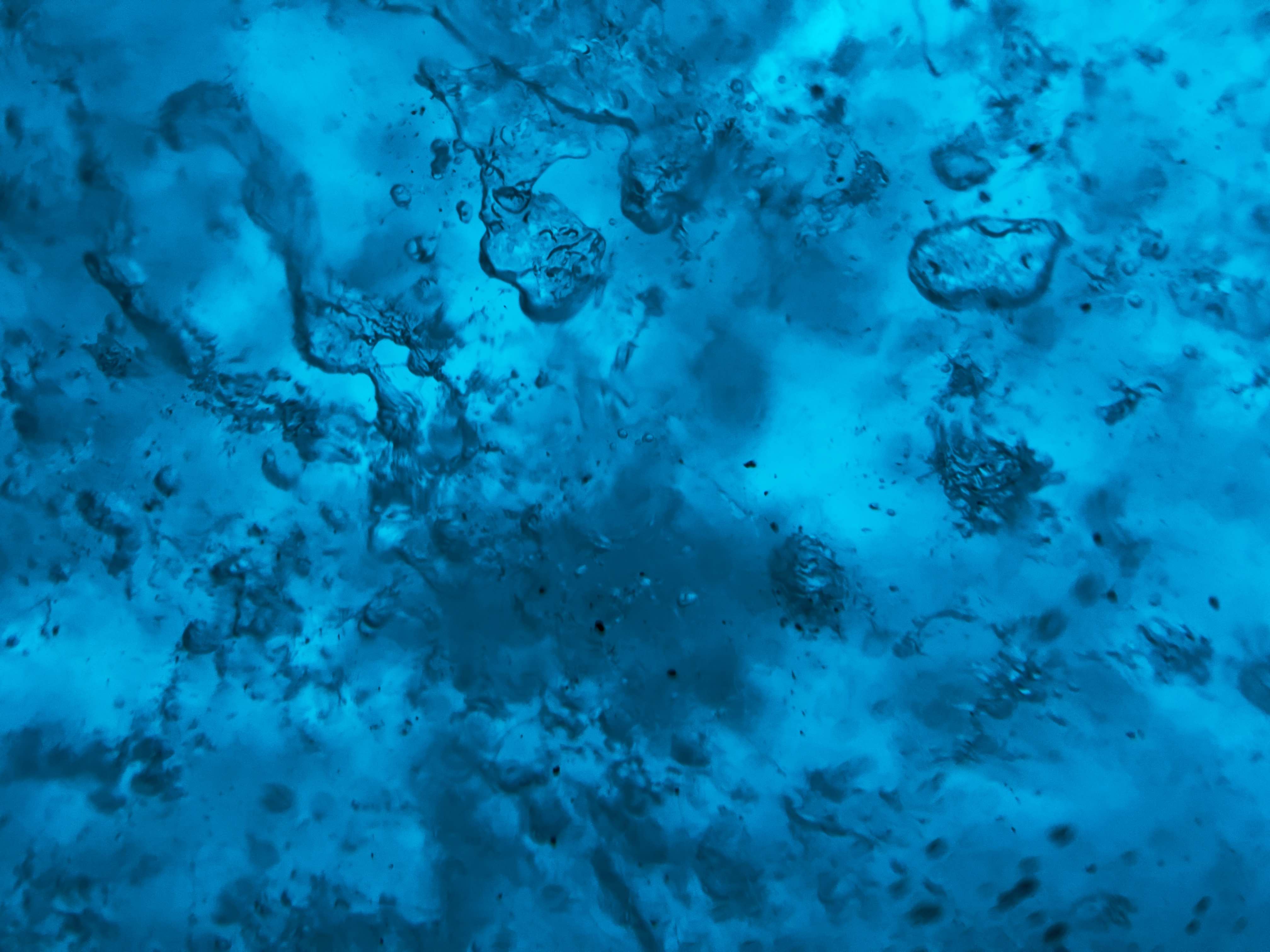

Capturing the magnificent sounds of calving glaciers

Beverly flew from New York to Iceland’s capital Reykjavik and then travelled on to Kulusuk in Greenland. He arrived in July, during the days of the midnight sun. Getting to the glaciers involved a two-hour boat ride from Kulusuk to travel even deeper into the Arctic. Here, he encountered ginormous glaciers such as the Knud Rasmussen and Karaale Glaciers.

“We would camp by the glaciers, then go back to Kulusuk to regroup for a few days, charge batteries, and then go out for another stretch,” Beverly explains. “The recording conditions were nearly perfect, as the temperatures were fairly mild at around five to six degrees Celsius and, with the sun that never sets in July, it was handy to be able to record at any time of the day. Sometimes nothing happened for 12 hours, sometimes there was a flurry of activity over a one-hour timespan, so it was very important to get the audio right every time the calving activity took place.

“Each glacier also has its own sonic personality,” says Beverly. “The width and height of the mountainous fjord also makes a big difference to the calving sounds, so the acoustics are different for each glacier. Karaale had more long roaring events as huge pieces broke loose and rolled. Knud had more thunderous gunshot-like cracks as pieces broke from the top and fell to dynamite the water below.”

Beverly had microphones placed on either side of the calving face of the glaciers he recorded. Between five and eight audio recording rigs were running 24 hours a day for 14 days.

“I have some small, lavalier mics that I run off my handheld recorders, and those use plug-in power of about five volts and can run continuously for over five days,” he says. “Then I have my main Sennheiser double mid-side rig, which runs on 48-volt phantom power. The three mics I use - a pair of MKH 8040s and an MKH 30-P48 - can run for roughly 18 hours on one battery. Generally, we would camp somewhere near one of the glaciers, so I’d have the Sennheiser double mid-side rig near the campsite recording the calving. Over the two weeks, I managed to capture about 700 of the calving events, which was astonishing.”

An event Beverly refers to as ‘biblical’ took place when he was camped on the edge of the fjord next to the Knud Glacier. “I was in my tent, almost asleep, when I heard a deep rumble. I’d heard these many times before on the trip, but I felt this one in my bones and it wasn’t tailing off, it was continuing to build. I quickly ripped open the tent and saw a piece of ice the size of a skyscraper break off the glacier. It boomed and roared with incredible power. The calving event thundered continuously for five minutes! Then the fjord crackled and popped for the following four hours as the icy debris broke and released bubbles. It was an awe-inspiring and bittersweet moment that I will never forget.”

Whilst calving is a natural behaviour of glaciers as gravity pulls the ice downhill, the rate of calving is increasing with climate change. “All of the glaciers I recorded in Greenland are currently retreating at an unprecedented rate. By recording the sounds of those spectacular calving events, I hope others can experience and love these living rivers of ice. The more people develop a visceral connection to the beautiful sounds of glaciers, the more likely we are to slow their retreat.” Sound Sample: https://soundcloud.com/trexbeverly/greenland-calving-calving-glaciers

Recording an ‘ice xylophone’

“There’s lots of interesting stuff happening out on the glacier apart from calving,” explains Beverly. “Together with my mountaineering guide, we did some ice climbing and rappelled down into some of the big crevasses to listen to the sounds happening down in the glacier.”

Here, Beverly found a fascinating natural phenomenon. “Occasionally, when glaciers split to create deep crevasses, thin flakes of ice still connect between walls. If you can find a crevasse with multiple flakes, a beautiful natural wonder occurs: the ice xylophone,” he explains. “It happens when you get ice on the top of the glacier called ‘sun crust’, similar to mojito ice made of tiny flakes. If you scrape those into the crevasse with an ice axe, something magical happens. The sun crust pings off the flakes on the way down with beautiful melodic tones! Each flake is a different size and at a different depth, so they have different audible pitches. These captivating melodies are one of the ways the glaciers sing, but they also sing with droning melodic tones.” https://soundcloud.com/trexbeverly/greenland-ice-xylophone

Ice caves

During the summer, glaciers are constantly melting, and the meltwater carves ice caves with fascinating acoustic properties. Beverly hung his microphones deep into crevasses and rappelled down himself: “I’d make stereo bars out of selfie sticks, attach the mics and recorder in a dry bag, and then drop the whole thing 25 metres down into a crevasse on a rope.”

What he had discovered was beyond fascinating. “I realized that glacial crevasses actually sing! I thought I was hearing things at first, but then I realized that the water was sometimes resonating in ice caves to create a collection of droning pitches. These could be light and airy or very deep and ominous.”

While exploring the area, he started to feel pulsing bass vibrations in his chest. “I had my two MKH 8020s set up and two Geofones stuck into the glacier. Suddenly, I started feeling this bass sound, it sounded like a subwoofer. My guide and I wandered around for a bit before we found the source, a deep jagged crevasse that was home to what I called the ‘breath of the glacier’, formed by a large moulin [a waterfall inside the glacier] that was creating large pockets of air in the sub-glacier river. These bubbles would burst out every few seconds and the sounds would resonate up through the crevasse like a sleeping dragon. It was wild!”

Luckily, Beverly was able to record the entire event, which only happened for 20 minutes. “I even left the rig overnight, but it only lasted for those first 20 minutes before the glacier shifted and the sound was gone. You wouldn’t think that those masses of ice can shift so quickly, but they really do. This can make leaving gear out on the glacier quite tricky. Usually, you would use a type of mountaineering ice screw, but in 24 hours even that becomes risky as the sun hits the ice screw and starts melting the surrounding ice. It took a lot of careful planning and constant checking on the gear to make sure nothing would shift or fall into a crevasse.”

“By using MKH 8020s together with Geofones, I was able to get the sounds of the glacier plus the sub-bass impact coming from the contact mics. And when you mix those together, you get these epic sounding events.”https://soundcloud.com/trexbeverly/greenland-ice-caves

Recording underwater icebergs

Beverly found yet another fascinating natural spectacle during his Greenland expedition – the magical underwater world of melting icebergs. “It’s very tricky to record underwater sounds,” he says. “Many hydrophone recordings I’ve made myself and heard from others are conceptually interesting because they show the unheard world below the waves, but they sound like tinny lo-fi recordings. That finally changed in Greenland with a combination of some wonderful DIY hydrophones and the amazing underwater acoustics of the rocky fjords.”

Beverly says that the underwater space makes just as much impact on the sound of the recording as the world above. “For example, if you record out in the middle of a giant fjord with a depth of 1000 metres, there is very little resonance. That’s the equivalent to recording on a flat prairie. However, find rocky fjords with depths ranging from 50 to 300 metres and they sound like cathedrals! The pinging and booming of the icebergs could be heard bouncing around the walls with wonderful echoes.”

One day, Beverly was using stereo hydrophones together with stereo MKH 8020s, recording the sounds both below and above the water with four channels. “Something really interesting happened while I was monitoring the two channels of the hydrophones in the water. When I was taking a break and had pulled my HD 280 PRO down around my neck, I suddenly heard a loud ‘boom’ come through the headphones, and I let out a yell. Thinking that I ruined the audio and being mad at myself for shouting, I checked the recording to find something truly fascinating. Because sound travels four to five times faster in water than air, what I had heard in my headphones was the iceberg breaking in half underwater. It came through the headphones first because the sound was moving so much faster underwater. The above-water boom arrived slightly after my yell, which was fabulous as it meant I hadn’t destroyed the recording with my audible reaction. Hearing the difference in the speed of sound in air versus the speed of sound in the water was amazing!” https://soundcloud.com/trexbeverly/greenland-underwater-icebergs

So, what’s next?

“I feel like I only scratched the surface of the wonderful world of glaciers,” says Beverly. “I have just returned from a new expedition to Iceland. I love the polar regions in general, so I’m very interested in doing more glacier recordings in Patagonia, and maybe eventually in Antarctica. Finding how much sound happens on the glacier was a revelation to me.”

Recording stories so others can tell theirs

With Beverly’s field recordings used by Oscar, Emmy, and Golden Reel award winning sound designers and sound editors like Peter Albrechtson, Tim Farrell, Stephen Flick, Stuart McCowan, Robert Stambler, and Russell Topal among others, as well as companies, museums, and universities, his unique material offer a limitless canvas of opportunities for sound creatives.

“I have been very fortunate to work with some of the world’s renowned sound professionals and help them tell their stories with the sounds that I record. Whether it’s a blockbuster movie, a nature documentary, a video game, or an art installation, the sound is the element that bonds the story together like a glue,” he concludes.

(Ends)

If you would like to read more about Beverly’s Greenland expedition, click this link.

You can download the images accompanying this media release and additional photos here.

All images and sound samples courtesy of Thomas Rex Beverly.

Follow Thomas Rex Beverly’s sound adventures here: https://thomasrexbeverly.com/